Helping the lonely child

As with any feeling, you just have to let kids feel it; it’s their journey to navigate.

“Culturally, we tend to shy away from acknowledging that children experience complex emotions. There’s an assumption that childhood should be a time of blissful innocence, but in reality, children are constantly making sense of the world, including its more difficult aspects.” Luke Kerridge

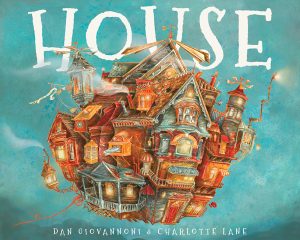

Luke Kerridge is a theatre maker and director, and co-creator of HOUSE, a book and play about loneliness. He and his co-creators, Dan Giovannoni and Charlotte Lane have tried to build a space where conversations about difficult subjects are made meaningful. And shying away from acknowledging or talking about loneliness, while often a ‘well-intentioned, protective instinct’ can often make the problem more ingrained.

Read the latest print edition of School News HERE

How do children experience loneliness?

“Children and adults are both fundamentally dealing with the same core feeling — the desire to connect and be understood,” explains Dan Giovannoni, the writer of more than 17 plays for children, teenagers and grown-ups. “The achy, stormy feelings that come with loneliness are the same. I think sometimes grown-ups have a broader context for understanding loneliness, while kids are still figuring that out.”

Giovannoni adds that while children often experience situational loneliness – when they don’t have someone to play with, or because they feel left out of a group – it can come to have “an existential quality, particularly for older kids as they begin to question where they fit in the world, how they relate to others, who they are. This can lead to more complex feelings of isolation.”

When writing the play, Giovannoni and Kerridge met with groups of children at various points, interested in their ideas about loneliness and how they experienced it.

“They expressed an experience and understanding of loneliness as a feeling of isolation or lacking social connection, but also as an emotion caused by a breadth of other causes, such as feeling misunderstood, feeling overwhelmed, being treated unjustly, or experiencing distress over societal, political, and global issues such as climate change,” explains Lane.

But children don’t always have the vocabulary to articulate exactly how they’re feeling or why, adds Kerridge, which can lead to disconnection or not feeling like you belong. “You’re still piecing together the world around you—and may not yet recognise the chain of cause and effect in your environment. Plus, your worldview is often shaped by your family, community, or the media. All of this can make for some pretty confusing or disorienting times.”

It’s interesting to point out that during their conversations with children, Kerridge and Giovannoni discovered that children didn’t always see being alone as a negative thing, that being alone and lonely were separate concepts. “What stood out, was how much their imaginations played a role. Many described using their imagination when they were alone – creating rich, imaginary worlds,” says Kerridge.

Why are adults terrified by a lonely child?

Lane believes that loneliness is distressing for adults to recognise in children as it suggests a breakdown in social connection, and it can be difficult to know how to support someone if these feelings are compromising their mental health.

Giovannoni agrees. “Grown-ups naturally feel a deep sense of responsibility toward children. There’s an instinct to protect. They see a child who’s lonely, and it triggers this fear that something’s wrong or that the child isn’t getting the connection and support they need.”

Yet, he adds, it’s important to let children experience it. “As with any feeling, you just have to let kids feel it – they have to go through the whole thing, the whole cycle. You can make them feel as safe as you can, arm them with resources and language and help build resilience – but it’s still their journey to navigate. At the end of the day, you can’t protect them from everything, and sometimes those feelings of loneliness help them grow, understand themselves better, and ultimately develop the strength to handle life’s ups and downs.”

This is why starting discussions about loneliness and creating spaces where children can connect is a vital way schools can help.

How can educators and schools help the lonely child?

“Opportunities to discuss feelings and experiences can help children to recognise and understand their own emotional complexity, find a language to express themselves, and develop coping mechanisms,” says Lane. Schools can do this by “providing inclusive and nurturing environments, encouraging supportive relationships, and truly listening and seeking to understand each other.”

“Taking inspiration from HOUSE, perhaps by creating safe, creative, and imaginative spaces where children can connect—whether that’s through clubs, special rooms, or events,” adds Kerridge.

“I’m also a strong advocate for involving children in the arts,” he says. “Stories have immense power; they can offer new perspectives and open up entirely different ways of seeing the world. Reading quality literature and taking children to the theatre is incredibly important. It shows them the power of imagination and how they can use it to make meaningful changes in their own lives.”

“A culture that prioritises emotional well-being, connection, inclusion and understanding can go a long way in helping children who are feeling lonely. Helping young people build resilience is important.” Dan Giovannoni

Children at the workshops explained that a safe space was often just a place where they could just ‘be themselves.’

Despite being surrounded by hundreds, sometimes even thousands of other children, young people often feel they don’t fit in at school. This, explains Kerridge, is what often leads to feelings of loneliness. “In HOUSE, the characters experience isolation and low self-esteem because they don’t feel they fit in anywhere. The beauty of the house, however, is that it creates a safe space where these so-called misfits can come together and find a sense of belonging.”

“The way other people see us and treat us can inform how we understand ourselves. If you don’t have people contributing to your understanding of yourself, I think it can be much harder to draw lines around your edges.´ Dan Giovannoni

Giovannoni says it’s unlikely we will ever eradicate feelings of loneliness and isolation in our young people, and adds that research indicates that it is on the rise. “But supporting all kids with coping mechanisms will help those experiencing loneliness to handle it more effectively and bounce back from challenging social situations.”

“We hope that this book offers a platform for conversation about loneliness; whether that be by helping to find a language to express intangible and complex emotions and ideas, or by normalising loneliness as a feeling that we all experience sometimes and can overcome,” said Lane.

House by Dan Giovannoni and Charlotte Lane is available through Fremantle Press. Teaching notes are also available here.